The case of trade on a global scale has evolved at an accelerated rate since the end of the Cold War, with the introduction of countless regional trade agreements between countries with shared borders becoming most prominent in the 21st century. The enhanced technological advancements have made international communication virtually effortless and has made globalization vastly more common allowing businesses to efficiently operate on an international scale. Through economic downturn, war and natural disaster, the global economy has nonetheless thrived as international relations grow. However, early 2020 would bring forth the most unprecedented, and economically destructive event in modern history. The global pandemic has not only brought economic hardship to many nations but has also put a halt to the efficient globalized supply chain that many economies rely on. This public health crisis has been the silent killer that has stunted global trade, causing many countries to initiate widespread lockdowns and implement combatting policy that would boost international debt to levels not seen since the second World War, causing a shortage of both demand and supply (Barlow, 2021). Although vaccination rates continue to rise globally and many countries begin to lift public health restrictions, there is a long road ahead to repair the decimated world economy. There are many factors that contributed to the decline of globalization during the span of the pandemic, and this report will work to outline these and to provide a better understanding of where they derived from, and to hopefully provide insight on how such hardship can be avoided in the future.

Aside from being a public health crisis, it can be assumed that globalization at large was otherwise at the forefront of the areas impacted by the pandemic. However, it is worth outlining where this occurred most prominently, and which sectors experienced sharper decline than others. The first topic to address is the role that the US dollar has played throughout this pandemic. The US dollar holds significant power on the world stage. Nearly 60% of international reserves are held in US dollar-denominated assets (Arslanalp, 2021). Evidently, the US dollar is one of the few areas where there was little, to no loss. This is because at the beginning of the pandemic, demand for the dollar spiked as investors sold off risky assets like stocks and held cash for protection. This did not just occur in the US. The dollar was in high demand by investors globally, and the United States Federal Reserve was forced to lend dollars to economies overseas to satisfy this demand. Instead of weakening the value of the dollar, this made it worth even more against foreign currencies and increased leverage for the US economy on a global scale as neighbouring countries struggled (Miller, 2020). This was harmful as their trading partners were taking excessive losses on exchange rates, making it extremely difficult for economies dependent on the US for certain goods to maintain a stable market during the recession. Moving on, it is apparent that one of the hardest hit areas was the health sector. A rapid increase in demand for medical supplies at the beginning of the pandemic produced a global supply shortage, which in turn caused an unprecedented, and virtually unavoidable spike in prices on goods such as ventilators, personal protective equipment, and various medicines (Barlow, 2021). Governments frantically worked to obtain supplies, and numerous countries that remained deficient repurposed manufacturing companies that began producing these goods domestically. With the shortage driving up retail prices on personal protective equipment and sanitization products, many jurisdictions in Canada implemented price gouging laws to drive prices on these goods back to pre-pandemic levels (Cowley, 2020). Another sector greatly affected by the pandemic, and that has a surprising impact on trade is travel and tourism.

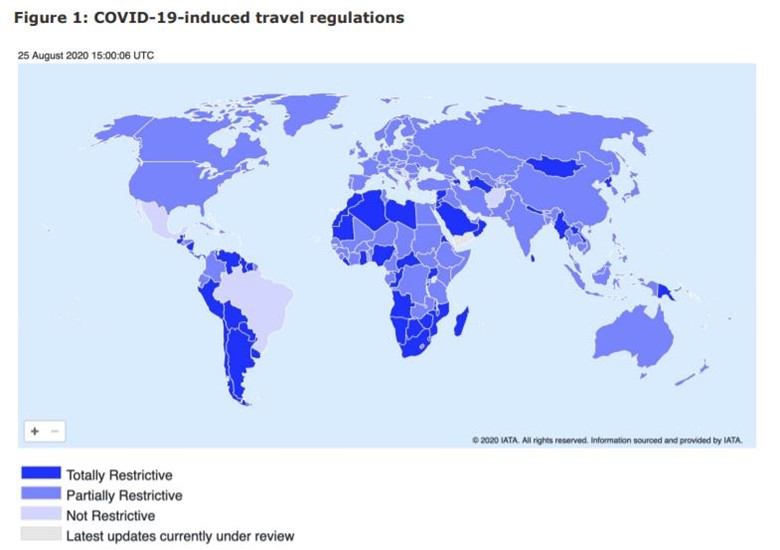

In August 2020, just prior to the beginning of the second wave of the virus in most countries, the majority of nations worldwide had either partially restrictive, or totally restrictive travel regulations (IATA, 2020). Tourism has accounted for 25% of net jobs created over the past five years globally and contributes to nearly one third of GDP in various Central American economies. This resulted in historically low performance in the travel and tourism sector globally. Members of the WTO attempted to promote domestic and regional tourism hoping to recover some of the loss, but the nations reliant on foreign tourism were devastated by this crisis (WTO, 2020). To continue the effect of the pandemic on cross-border mobility, in the beginning of the fall 2020 school year, international enrollments dropped by 43% (Redden, 2020). For countries that have a significant outflow of students studying abroad such as China and India, this decline brought a considerable drop in exports of education services (WTO, 2020). This decline forced a shift in the education sector. International students retained the ability to study at foreign colleges and universities by doing so “remotely”. In the first half of 2020, global education technology saw it’s second largest investment period at $4.5 billion as educational institutions made the move to online, “remote” learning (HolonIQ, 2020). This “new normal”, as it was called, came with large scale shifts in consumption by many economies as many aspects of life primarily occurred at home. Along with remote learning, many employees all over the world worked from home to slow the spread of the virus, creating unprecedented demand for cell phones, laptops, and office furniture, among many other goods. A study completed by the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC) in early 2021 showed that laptop imports in the United States rose by 85%, cellphones by 48%, and headphones by a staggering 615%, giving China an opportunity to take advantage of this spike in demand (Garcia, 2021). This increase in imports to North America resulted in stressed cargo terminals in the US creating backlog, with an inability to send shipping containers back to Asia quickly enough to keep up. This delayed economic activity and greatly disrupted trade, impeding the ability for countries to efficiently move shipping containers around the world, causing shortages of these goods (Garcia, 2021).

To further discuss the topic of supply chain disruption, the regional impacts can be broken down as this was an area that was very heavily conflicted given the uncertainty of the severity of the virus at the beginning of the outbreak. Many countries imposed strict measures to their supply chain processes as a defense mechanism against the spread of the pandemic.

The above figure outlines the stringency that various countries used when exporting and importing goods. The top graph shows the weighted index of imports and exports by ship through a seven-month period, and the bottom graph shows the stringency used in supply chain processes over the same period (Verschuur, 2021). It can be observed that there was a sharp incline in stringency by China during the onset of the outbreak in Wuhan in January, and their trading partners followed suit in March when the virus made its way overseas. This was followed by gradual easing in stringency among all nations as familiarity with the virus increased in the summer of 2020. This data can be tied back to the spike in demand previously mentioned due to digital transformation, and how China seemingly took advantage of this. The top graph shows a sudden decrease in their supply chain stringency immediately following initial lockdowns in the US, UK, and South Africa as consumer needs shifted and Chinese exports adapted. This is an event that was almost certainly inevitable given the ambiguity of the situation, but nevertheless had dire consequences for supply chain processes globally.

As active coronavirus cases decline globally, and countries begin easing public health restrictions and begin focusing fiscal and monetary policy on economic recovery as opposed to defense against the virus, globalization is beginning to rebound, and hard-hit sectors are recovering. Despite the widespread devastation in 2020, the global economy is on pace to see its strongest post-recession recovery in 80 years in 2021, expecting 5.6% growth. This is largely a result of the rapid recovery of large, developed economies like the US and China, who are each poised to contribute to 25% of global growth in 2021 (World Bank Group, 2021). Developed countries will be among the first to fully vaccinate their populations, allowing them to effectively contain the spread of the virus, and focus on a robust economic recovery. However, this rapid recovery comes with surging inflation in many countries, as the financial support from governments and emergency monetary policy have caused the value of their respective currency to diminish. This affects trade in many ways, because the accelerated rate at which larger countries reopen their economies results in a sharp influx of demand, causing supply shortages, raising prices of commodities and energy (Carosa, 2021). This has happened for two reasons. The first being that consumers spent very little money in 2020 due to the pandemic, so there is a sudden spike in spending, primarily on retail goods and travel, and the second reason being that interest rates remain low, almost at zero percent, spurring demand in real estate (Carosa, 2021). The difference between the pandemic recession and previous financial recessions is the widespread impact that the lockdowns had on access to goods and services. The coronavirus pandemic caused an induced recession due to the shut down of the global economy as a defense tactic. Governments decided to lockdown their countries for the safety of their citizens, which also means that governments made the decision to reopen the economy as well. The controlled fashion in which this economic downturn occurred allowed for an accelerated rebound. The initial decline in global stock markets stemmed from panic among investors because the event was unique. Once nations established a grasp on the situation, they could begin a strong recovery.

The graph above paints a perfect picture to describe this. Global trade recovered substantially quicker after the 2020 recession, taking only four quarters to nearly reach pre-pandemic levels (UNCTAD, 2021). This demonstrates how efficiently the global economy was able to adapt to the conditions and modify policies to adhere to the needs of the “new normal”.

To conclude, it is worth noting that the pandemic, though still an ongoing crisis globally, is beginning to ease and allow economies to build up recovery. There were sectors that were hit harder than others, and regions of the world that were hit harder than others, so policies put into place to stimulate globalization once again should be regionalized, and should fit both the immediate, and future needs of the economy domestically. First, national banks in large, developed economies should consider raising interest rates in the second quarter of 2022. Many nations, prominently in North America, are experiencing record inflation rates coming out of the pandemic due to widespread, and sudden spikes in demand, especially in real estate. With housing prices in North America having hit growth levels not seen in decades before the pandemic started, it is crucial that this demand be met with monetary policy as well as government intervention, such as restricting foreign residential real estate investment. Although economies will be urged to welcome foreigners in a time when international relations have been so heavily regulated, it is crucial that governments and national banks do their part to avoid any form of an inflation crisis that will most likely stem from the housing market. Second, many economies worldwide saw widespread loss on the value of their currency because of the inflated value of the US dollar resulting from high demand. The responsibility now lies in the hands of the United States Federal Reserve to restrict the outflow of the dollar to restore its true value on a global scale. The leverage that the US dollar holds may seem advantageous domestically, but it will begin to harm the country’s relations with their trading partners as the price of their exports rise. Finally, it is evident that the major concern in the past year has been public health. The reason that global trade took a turn for the worst is nothing more than the presence of fear of spreading a deadly virus. This proves that the global economy must establish measures to avoid a crisis such as this from repeating itself. This means the world’s largest economies must work toward finding methods to implement emergency policy to drive supply and demand toward equilibrium when large scale devastation occurs. This may include putting premeditated plans in place to repurpose individual sectors, ensuring that they have the tools at their disposal to sharply increase supply of a certain good or service should it be necessary. Looking back, there are undoubtedly countless ways that the global economy could have better prepared for such an event had there been prior knowledge of its outcome. Nevertheless, this should be seen as an opportunity to plan for an effective and efficient reaction to future viral outbreaks, and as costly as it may be, it will assist in avoiding unnecessary harmful effects to global trade, and to the global economy overall.

References

$4.5B Global EdTech Venture Capital for 1H 2020. (2020, July 10). Retrieved from https://www.holoniq.com/notes/4.5b-global-edtech-venture-capital-for-q1-2020/

Arslanalp, S. (2021, May 13). US Dollar Share of Global Foreign Exchange Reserves Drops to 25-Year Low. Retrieved from https://blogs.imf.org/2021/05/05/us-dollar-share-of-global-foreign-exchange-reserves-drops-to-25-year-low/

Barlow, P. (2021, February 1). COVID-19 and the collapse of global trade: Building an effective public health response. Retrieved from https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(20)30291-6/fulltext

Carosa, C. (2021, August 24). Covid Or Policy: What’s Causing This Inflation Surge? Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/chriscarosa/2021/08/23/covid-or-policy-whats-causing-this-inflation-surge/?sh=75a250c64c0f

COVID-19 Travel Regulations Map* (powered by Timatic). (2020, August 25). Retrieved from https://www.iatatravelcentre.com/world.php

Cowley, J. (2020, November 21). Provinces promised crackdown on pandemic price gouging. In fact, there have been few repercussions | CBC News. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/pandemic-price-gouging-1.5806500

Cross-Border Mobility, COVID-19 and Global Trade. (2020). Covid-19 Reports. Retrieved from https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/covid19_e/mobility_report_e.pdf.

Garcia, G. (2021, October). The Supply Chain Was Messy. Then COVID Happened. Retrieved from https://oec.world/en/blog/post/covid-19-supply-chain-disruption

Global trade’s recovery from COVID-19 crisis hits record high. (2021, May 19). Retrieved from https://unctad.org/news/global-trades-recovery-covid-19-crisis-hits-record-high

Miller, C. (2020, May 13). The Dominance of the U.S. Dollar During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.fpri.org/article/2020/05/the-dominance-of-the-u-s-dollar-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

Redden, E. (2020, November 16). Survey: New international enrollments drop by 43 percent this fall. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/11/16/survey-new-international-enrollments-drop-43-percent-fall

Verschuur, J., Koks, E. E., & Hall, J. W. (2021, February 25). Observed impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on global trade. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-021-01060-5

World Bank Group. (2021, June 09). Global Economic Prospects: The Global Economy: On Track for Strong but Uneven Growth as COVID-19 Still Weighs. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2021/06/08/the-global-economy-on-track-for-strong-but-uneven-growth-as-covid-19-still-weighs